Santa Sabina College, Strathfield is located on The Boulevarde, Strathfield and is a Catholic school for girls.

Santa Sabina College is known for its many fine and historic buildings. One of the most prominent buildings is ‘Holyrood’, located near the corner of Jersey Road, facing The Boulevarde. This building features the façade of the former City Bank, which was formerly located on the corner of Pitt and Moore Streets, Sydney. However, following a fire in 1890, the façade was moved stone-by-stone to Strathfield and added as a façade to an existing residential property, owned by Charles Hoskins.

The City Bank building was designed by architect George Mansfield and built in 1873. It was described on completion as ‘one of the architectural gems of Sydney … The front which is composed of a rich coloured sandstone, is Italian in style, perhaps the term Italian-Gothic would more accurately describe it. A considerable ornament to the streets of Sydney’.

The Bank building had created great interest because of the precautions against fire incorporated into the design of the building. All the main parts of the buildings were inter-connected by doors for quick escape from a fire, and a fire-hose connected to the water main in Pitt Street was a striking innovation in the days before universal fire regulations. The edifice was divided into two, a building within a building, with walls averaging six feet through, iron doors, ceilings of arched stone and not a particle of wood used in any part of the construction.

Fire broke out at 2am on 2 October 1890 in the premises of Messrs. Gibbs, Shallard and Co, a printing firm. The fire, known as the Great Fire being the largest in Australia at this time, spread quickly and within two hours consumed the whole block bounded by Moore, Pitt and Castlereagh Streets and Hosking Place. The area extended over 11,000 square yards, or about 2¼ acres. In the subsequent city improvement plans razed the ruins which cleared the way for the creation of the modern Martin Place (built on the former Moore Street).

The Great Fire burned all day and into the following day, was attended by seventeen professional and voluntary fire brigades. It attracted so many spectators that police, troopers and special constables were on duty. The damage was estimated at ‘three quarters of a million Sterling’ and the intensity of the fire can be gauged by the fact that even the City Bank did not escape destruction – water causing considerable damage.

The buildings which were destroyed and damaged comprised Gibbs, Shallard, and Company’s printing and publishing establishment, Castlereagh-street; Lark, Sons, and Company, Moore-street; Feldheim, Gotthelf, and Company, Moore-street; The City Bank, Pitt and Moore streets; Richardson and Wrench, Pitt-street; Henry Bull and Company, Pitt-street; Cyrus Mason, and Company, Pitt-street; Joseph Palmer, Pitt-street; Eldon Chambers; Christopher Newton and Company, Pitt-street; the Athenaeum Club, Castlereagh-Street; Lawson Brothers and Jones, and the Southern Club, Castlereagh-street.

The standing stone work or façade of the burnt City Bank attracted the attention of Charles Hoskins, an iron and steel manufacturer. He decided to purchase it and remove it stone by stone to his building site on The Boulevarde Strathfield. The façade was re-assembled to form the front part of his residence, so grand that the home was named ‘Illyria’ after the home of so many great Roman emperors.

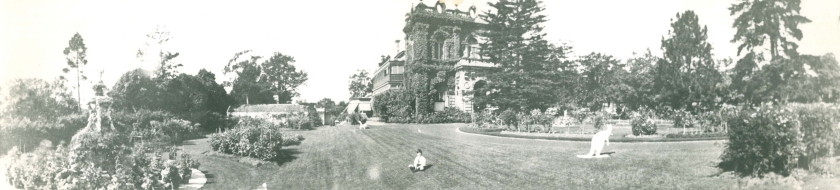

A more conventional Italianate building completed the residence. As the land faced the same aspect as the Pitt Street block on which the Bank stood, the pattern of light and shade is as Mansfield envisioned it. Added to that effect, Charles Hoskins complemented it with a beautifully landscaped area including a circular drive and very beautiful trees.

For sixteen years the Hoskins family lived happily at ‘Illyria’, Charles Hoskins engrossed by his infatuation with motor cars. He purchased a two-cylinder horizontal engine Ford in 1904, the second Ford to be imported into Australia. This was followed with a succession of fine classic cars including a 1908 Clement-Talbot. It is understood that the garage suite at the rear of the house, accessible from Jersey Road, was built during Hoskins time for his vehicles, which would make it one of the earliest garages in Sydney.

As the steel industry grew the family moved in 1908 to the Lithgow area to be closer to their interests.

In 1911 William J. Adams, of the ‘Tatterstall’s Hotel’ bought ‘the City Bank house’ as it was locally known and his family lived there for twenty-five years. Adams renamed it ‘Holyrood’ because the family felt it resembled Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Alterations were made to the interior where rooms now became Art Nouveau in style. Leadlight windows, white tiling in the kitchen and bathrooms with elaborate friezes and a billiard room with lantern—roof were introduced. Additions included a conservatory, new service rooms and new front gates with Holyrood included in the design of the metal work and large seafaring lanterns atop the pillars.

When the Adams family left Holyrood in 1936 the residence was offered to the Dominican Sisters who had established Santa Sabina College in 1894 on a six hectare site next door. It was an opportunity to provide dormitory accommodation for senior students and so it has continued through the years as suitable for music and art teaching and as a Deaf Education Centre.

It has also proved very complementary to the imposing Dutch Renaissance styled, rose brick buildings with terracotta mouldings, erected by the College. An imported terracotta panel in the tower shows St. Dominic as a dog bearing in its mouth a lighted torch.

The building ‘Santa Casa’ was once located at the rear of Holyrood, but was demolished in 1993.

References

Emilsen, S. (1994). Dancing St Doom’s Plot – History of Santa Sabina and Santa Maria del Monte Strathfield, Santa Sabina Ltd.

The Great Fire. (1890, October 18). Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 – 1919), p. 32. Retrieved August 21, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71183348

The Great Fire in Sydney. (1890, October 8). Macleay Argus (Kempsey, NSW : 1885 – 1907; 1909 – 1910; 1912 – 1913; 1915 – 1916; 1918 – 1954), p. 3. Retrieved August 20, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article234088178

The Great Fire (1890, October 3). The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW : 1883 – 1930), p. 4. Retrieved August 24, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article235799046

The Great Fire. (1890, October 15). The Australian Star (Sydney, NSW : 1887 – 1909), p. 5. Retrieved August 31, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article227462451

Big Fire in the City. (1890, October 4). Illawarra Mercury (Wollongong, NSW : 1856 – 1950), p. 3. Retrieved September 24, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article132639235

Parsons, George, ‘Hoskins, Charles Henry (1851–1926)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hoskins-charles-henry-6738/text11639, published first in hardcopy 1983, accessed online 31 October 2022.

The Moore-Street Fire (1901, July 11), The Moore-Street Fire, Evening News, p3

THE TERRIBLE FIRE IN SYDNEY. GREAT DESTRUCTION OF PROPERTY. (1890, October 11). Illustrated Sydney News (NSW : 1881 – 1894), p. 18. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article63615678

No title (1890, October 11). The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 – 1912), p. 814. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article163650269